CHAPTER 3 (The Story of the Stone-translated by David Hawkes)

- Posted on: 2023-01-25

- |

- Views: 309

- |

- Category:

- ▸ The Story of the Stone

CHAPTER 3

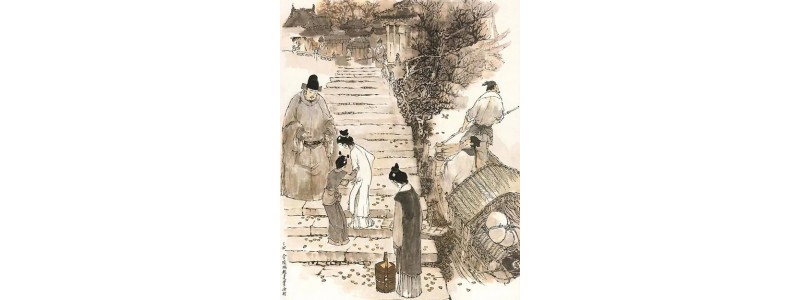

Lin Ru-hai recommends a private tutor

to his brother-in-law

And old Lady Jia extends a compassionate welcome

to the motherless child

When Yu-cun turned to look, he was surprised to see that it was Zhang Ru-gui, a former colleague who had been cashiered at the same time and for the same reason as himself. Zhang Ru-gui was a native of these parts, and had been living at home since his dismissal. Having just wormed out the information that a motion put forward in the capital for the reinstatement of ex-officials had been approved, he had been dashing about ever since, pulling strings and soliciting help from potential backers, and was engaged in this activity when he unexpectedly ran into Yu-cun. Hence the tone of his greeting.

As soon as they had finished bowing to each other, Zhang Ru-gui told Yu-cun the good news) and after further hurried conversation they went their separate ways.

Leng Zi-xing, who had overheard the news, proposed a plan. Why should not Yu-cun ask his employer Lin Ru-hai to write to his brother-in-law Jia Zheng in the capital and enlist his support on his, Yu-cun's, behalf? Yu-cun agreed to follow this suggestion, and presently the two friends separated.

Back in his quarters, Yu-cun quickly hunted out a copy of the Gazette, and having satisfied himself that the news was authentic, broached the matter next day with Lin Ru-hai.

"It so happens that an opportunity of helping you has just presented itself," said Ru-hai. "Since my poor wife passed on, my mother-in-law in the capital has been worried about the little girl having no one to look after her, and has already sent some of her folk here by barge to fetch her away. The only reason she has so far not gone is that she has not been quite recovered from her illness. I was, however, only just now thinking that the moment to send her had arrived. And as I have Still done nothing to repay you for your kindness in tutoring her for me, you may be sure that now this opportunity has presented itself I shall do my very best to help you.

"As a matter of fact, I have already made a few arrangements. I have written this letter here entrusting my brother-in4aw with your affair, explaining my indebtedness to you and urging him to see it properly settled. I have also made it quite clear in my letter that any expenses which may be involved are to be taken care of; so you have nothing to worry about on that account."

Yu-cun made an elaborate bow to his patron and thanked him profusely. He then ventured a question.

"I am afraid I do not know what your relation's position is at the capital. Might it not be a little embarrassing for a person in my situation to thrust himself upon him?"

Ru-hai laughed. "You need have no anxiety on that score. My brothers-in-law in the capital are your own kinsmen. They are grandsons of the former Duke of Rong-guo. The elder one, Jia She, is an hereditary official of the First Rank and an honorary colonel; the younger one, Jia Zheng, is an Under Secretary in the Ministry of Works. He takes very much after his late grandfather: a modest, generous man, quite without the arrogance of the pampered aristocrat. That is why I have addressed this letter to him. If I did not have complete confidence in his willingness to help you, I should not have put your honour at risk by soliciting him; nor, for that matter, should I have taken the trouble to write the letter."

Yu-cun now knew that what Zi-xing had told him was the truth and he thanked Lin Ru-hai once again.

"I have fixed the second day of next month for my little girl's journey to the capital," said Ru-hai. "If you cared to travel with her, it would be convenient for both of us."

Yu-cun accepted the suggestion with eager deference. Everything, he thought to himself, was turning out very satisfactorily. Ru-hai for his part set about preparing presents for his wife's family and parting gifts for Yu-cun, all of which Yu-cun in due course took charge of.

At first his little pupil could not be persuaded to part from her father; but her grandmother was insistent that she should go, and Ru-hai added his own reasons.

"I'm half a century old now, my dear, and I have no intention of taking a second wife; so there will be no one here to act as a mother to you. It isn't, either, as if you had sisters who could help to take care of you. You know how often you are poorly. And you are still very young. It would be a great weight off my mind to know that you had your Grandmother Jia and your uncles" girls to fall back on. I really think you ought to go."

After this Dai-yu could only take a tearful leave of her father and go down to the boat with her nurse and the old women from the Rong mansion who had been sent to fetch her. There was a separate boat for Yu-cun and a couple of servant-boys to wait on him, and he too now embarked in the capacity of Dai-yu's escort.

In due course they arrived in the capital, and Yu-cun, dressed in his best and with the two servant-boys at his heels, betook himself to the gate of the Rong mansion and handed in his visiting-card, on which he had been careful to prefix the word "kinsman" to his own name. By this time Jia Zheng had already seen his brother-inlaw's letter, and accorded him an interview without delay.

Yu-cun's imposing looks and cultivated speech made an excellent impression on Jia Zheng, who was in any case always well-disposed towards scholars, and preserved much of his grandfather's affability with men of letters and readiness to help them in any sort of trouble or distress. And since his own inclinations were in this case reinforced by his brother-in-law's strong recommendation, the treatment he extended to Yu-cun was exceptionally favourable. He exerted himself on his behalf to such good effect that on the very day his petition was presented Yu-cun's reinstatement was approved, and before two months were Out he was appointed to the magistracy of Ying-tian-fu in Nanking. Thither, having chosen a suitable day on which to commence his journey, and having first taken his leave of Jia Zheng, he now repaired to take up his duties.

But of him, for the time being, no more.

*

On the day of her arrival in the capital, Dai-yu stepped ashore to find covered chairs from the Rong mansion for her and her women and a cart for the luggage ready waiting on the quay.

She had often heard her mother say that her Grandmother Jia's home was not like other people's houses. The servants she had been in contact with during the past few days were comparatively low-ranking ones in the domestic hierarchy, yet the food they ate, the clothes they wore, and everything about them was quite out of the ordinary. Dai-yu tried to imagine hat the people who employed these superior beings must be like. When she arrived at their house she would have to watch every step she took and weigh every word she said, for if she put a foot wrong they would surely laugh her to scorn.

Dai-yu got into her chair and was soon carried through the city walls. Peeping through the gauze panel which served as a window, she could see streets and buildings more rich and elegant and throngs of people more lively and numerous than she had ever seen in her life before. After being carried for what seemed a very great length of time, she saw, on the north front of the east-west street through which they were passing, two great stone lions crouched one on each side of a triple gateway whose doors were embellished with animal-heads. In front of the gateway ten or so splendidly dressed flunkeys sat in a row. The centre of the three gates was closed, but people were going in and out of the two side ones. There was a board above the centre gate on which were written in large characters the words:

NING-GUO HOUSE

Founded and Constructed by

Imperial Command

Dai-yu realized that this must be where the elder branch of her grandmother's family lived. The chair proceeded some distance more down the street and presently there was another triple gate, this time with the legend

RONG-GUO HOUSE

above it.

Ignoring the central gate, her bearers went in by the western entrance and after traversing the distance of a bow-shot inside, half turned a corner and set the chair down. The chairs of her female attendants which were following behind were set down simultaneously and the old women got out. The places of Dai-yu's bearers were taken by four handsome, fresh-faced pages of seventeen or eighteen. They shouldered her chair and, with the old women now following on foot, carried it as far as an ornamental inner gate. There they set it down again and then retired in respectful silence. The old women came forward to the front of the chair, held up the curtain, and helped Dai-yu to get out.

Each hand resting on the outstretched hand of an elderly attendant, Dai-yu passed through the ornamental gate into a courtyard which had balustraded loggias running along its sides and a covered passage-way through the centre. The foreground of the courtyard beyond was partially hidden by a screen of polished marble set in an elaborate red sandalwood frame. Passing round the screen and through a small reception hall beyond it, they entered the large courtyard of the mansion's principal apartments. These were housed in an imposing five-frame building resplendent with carved and painted beams and rafters which faced them across the courtyard. Running along either side of the courtyard were galleries hung with cages containing a variety Of different-coloured parrots, cockatoos, white-eyes, and other birds. Some gaily-dressed maids were sitting on the steps of the main building opposite. At the appearance of the visitors they rose to their feet and came forward with smiling faces to welcome them.

"you've come just at the right time! Lady Jia was only this moment asking about you."

Three or four of them ran to lift up the door-curtain, while another of them announced in loud tones,

"Miss Lin is here!"

As Dai-yu entered the room she saw a silver-haired old lady advancing to meet her, supported on either side by a servant. She knew that this must be her Grandmother Jia and would have fallen on her knees and made her kotow, but before she could do so her grandmother had caught her in her arms and pressing her to her bosom with cries of "My pet!" and "My poor lamb!" burst into loud sobs, while all those present wept in sympathy, and Dai-yu felt herself crying as though she could never stop. It was some time before those present succeeded in calming them both down and Dai-yu was at last able to make her kotow.

Grandmother Jia now introduced those present.

"This is your elder uncle's wife, Aunt Xing. This is your Uncle Zheng's wife, Aunt Wang. This is Li Wan, the wife of your Cousin Zhu, who died."

Dai-yu kowtowed to each of them in turn.

"Call the girls!" said Grandmother Jia. "Tell them that we have a very special visitor and that they need not do their lessons today."

There was a cry of "Yes ma'am" from the assembled maids, and two of them went off to do her bidding.

Presently three girls arrived, attended by three nurses and five or six maids.

The first girl was of medium height and slightly plumpish, with cheeks as white and firm as a fresh lychee and a nose as white and shiny as soap made from the whitest goose-fat. She had a gentle, sweet, reserved manner. To look at her was to love her.

The second girl was rather tall, with sloping shoulders and a slender waist. She had an oval face under whose well-formed brows large, expressive eyes shot Out glances that sparkled with animation. To look at her was to forget all that was mean or vulgar.

The third girl was undersized and her looks were still somewhat babyish and unformed.

All three were dressed in identical skirts and dresses and wore identical sets of bracelets and hair ornaments.

Dai-yu rose to meet them and exchanged curtseys and introductions. When she was seated once more, a maid served tea, and a conversation began on the subject of her mother: how her illness had started, what doctors had been called in, what medicines prescribed, what arrangements had been made for the funeral, and how the mourning had been observed. This conversation had the foreseeable effect of upsetting the old lady all over again.

"Of all my girls your mother was the one I loved the best," she said, "and now she's been the first to go, and without my even being able to see her again before the end. I can't help being upset!" And holding fast to Dai-yu's hand, she once more burst into tears. The rest of the company did their best to comfort her, until at last she had more or less recovered

Everyone's attention now centred on Dai-yu. They observed that although she was still young, her speech and manner already showed unusual refinement. They also noticed the frail body which seemed scarcely strong enough to bear the weight of its clothes, but which yet had an inexpressible grace about it, and realizing that she must be suffering from some deficiency, asked her what medicine she took for it and why it was still not better.

"I have always been like this," said Dai-yu. "I have been taking medicine ever since I could eat and been looked at by ever so many well-known doctors, but it has never done me any good. Once, when I was only three, I can remember a scabby-headed old monk came and said he wanted to take me away and have me brought up as a nun; but of course, Mother and Father wouldn't hear of it. So he said, 'Since you are not prepared to give her up, I am afraid her illness will never get better as long as she lives. The only way it might get better would be if she were never to hear the sound of weeping from this day onwards and never to see any relations other than her own mother and father. Only in those conditions could she get through her life without trouble.' Of course, he was quite crazy, and no one took any notice of the things he said. I'm still taking Ginseng Tonic Pills."

"Well, that's handy," said Grandmother Jia. "I take the Pills myself. We can easily tell them to make up a few more each time."

She had scarcely finished speaking when someone could be heard talking and laughing in a very loud voice in the inner courtyard behind them.

"Oh dear! I'm late," said the voice. "I've missed the arrival of our guest."

"Everyone else around here seems to go about with bated breath," thought Dai-yu. "Who can this new arrival be who is 50 brash and unmannerly?"

Even as she wondered, a beautiful young woman entered from the room behind the one they were sitting in, surrounded by a bevy of serving women and maids. She was dressed quite differently from the others present, gleaming like some fairy princess with sparkling jewels and gay embroideries.

Her chignon was enclosed in a circlet of gold filigree and clustered pearls. It was fastened with a pin embellished with a fying phoenixes, from whose beaks pearls were suspended On tiny chains.

Her necklet was of red gold in the form of a coiling dragon. Her dress had a fitted bodice and was made of dark red silk damask with a pattern of flowers and butterflies in raised gold thread.

Her jacket was lined with ermine. It was of a slate-blue stuff with woven insets in coloured silks.

Her under-skirt was of a turquoise-coloured imported silk crêpe embroidered with flowers.

She had, moreover,

eyes like a painted phoenix,

eyebrows like willow-eaves,

a slender form,

seductive grace;

the ever-smiling summer face

of hidden thunders showed no trace;

the ever-bubbling laughter started

almost before the lips were parted.

"You don't know her," said Grandmother Jia merrily. "She's a holy terror this one. What we used to call in Nanking a 'peppercorn'. You just call her 'Peppercorn Feng'. She'll know who you mean!"

Dai-yu was at a loss to know how she was to address this Peppercorn Feng until one of the cousins whispered that it was "Cousin Lian's wife", and she remembered having heard her mother say that her elder uncle, Uncle She, had a son called Jia Lian who was married to the niece of her Uncle Zheng's wife, Lady Wang. She had been brought up from earliest childhood just like a boy, and had acquired in the schoolroom the somewhat boyish-sounding name of Wang Xi-feng. Dai-yu accordingly smiled and curtseyed, greeting her by her correct name as she did so.

Xi-feng took Dai-yu by the hand and for a few moments scrutinized her carefully from top to toe before conducting her back to her seat beside Grandmother Jia.

"She's a beauty, Grannie dear! If I hadn't set eyes on her today, I shouldn't have believed that such a beautiful creature could exist! And everything about her so distingue"! She doesn't take after your side of the family, Grannie. She's more like a Jia. I don't blame you for having gone on so about her during the past few days - but poor little thing! What a cruel fate to have lost Auntie like that!" and she dabbed at her eyes with a handkerchief.

"I've only just recovered," laughed Grandmother Jia. "Don't you go trying to start me off again! Besides, your little cousin is not very strong, and We've only just managed to get her cheered up. So let's have no more of this!"

In obedience to the command Xi-feng at once exchanged her grief for merriment.

"Yes, of course. It was just that seeing my little cousin here put everything else out of my mind. It made me want to laugh and cry all at the same time. I'm afraid I quite forgot about you, Grannie dear. I deserve to be spanked, don't I?"

She grabbed Dai-yu by the hand.

"How old are you dear? Have you begun school yet? You mustn't feel home sick here. If there's anything you want to eat or anything you want to play with, just come and tell me. And you must tell me if any of the maids or the old nannies are nasty to you."

Dai-yu made appropriate responses to all of these questions and injunctions.

Xi-feng turned to the servants.

"Have Miss Lin's things been brought in yet? How many people did she bring with her? you'd better hurry up and get a couple of rooms swept out for them to rest in."

While Xi-feng was speaking, the servants brought in tea and various plates of food, the distribution of which she proceeded to supervise in person.

Dai-yu noticed her Aunt Wang questioning Xi-feng on the side:

"Have this month"s allowances been paid out yet?"

"Yes. By the way, just now I went with some of the women to the upstairs storeroom at the back to look for that satin. We looked and looked, but we couldn't find any like the one you described yesterday. Perhaps you misremembered."

"Oh well, if you can't find it, it doesn't really matter," said Lady Wang. Then, after a moment's reflection, "you'd better pick out a couple of lengths presently to have made up into clothes for your little cousin here. If you think of it, send someone round in the evening to fetch them!"

"It's already been seen to. I knew she was going to arrive within a day or two, so I had some brought out in readiness. They are waiting back at your place for your approval. If you think they are all right, they can be sent over straight away."

Lady Wang merely smiled and nodded her head without saying anything.

The tea things and dishes were now cleared away, and Grandmother Jia ordered two old nurses to take Dai-ya round to see her uncles; but Uncle She's wife, Lady Xing, hurriedly rose to her feet and suggested that it would be more convenient if she were to take her niece round herself.

"Very well," said Grandmother Jia. "You go now, then. There is no need for you to come back afterwards."

So having, together with Lady Wang, who was also returning to her quarters, taken leave of the old lady, Lady Xing went off with Dai-yu, attended across the courtyard as far as the covered way by the rest of the company.

A carriage painted dark blue and hung with kingfisher-blue curtains had been drawn up in front of the ornamental gateway by some pages. Into this Aunt Xing ascended hand in hand with Dai-yu. The old women pulled down the carriage blind and ordered the pages to take up the shafts, the pages drew the carriage into an open space and harnessed mules to it, and Dai-yu and her aunt were driven Out of the west gate, eastwards past the main gate of the Rong mansion, in again through a big black4acquered gate, and up to an inner gate, where they were set down again.

Holding Dai-yu by the hand, Aunt Xing led her into a courtyard in the middle of what she imagined must once have been part of the mansion's gardens. This impression was strengthened when they passed through a third gateway into the quarters occupied by her uncle and aunt; for here the smaller scale and quiet elegance of the halls, galleries and loggias were quite unlike the heavy magnificence and imposing grandeur they had just come from, and ornamental trees and artificial rock formations, all in exquisite taste, were to be seen on every hand.

As they entered the main reception hall, a number of heavily made-up and expensively dressed maids and concubines, who had been waiting in readiness, came forward to greet them.

Aunt Xing asked Dai-yu to be seated while she sent a servant to call Uncle She. After a considerable wait the servant returned with the following message:

"The Master says he hasn't been well these last few days, and as it would only upset them both if he were to see Miss Lin now, he doesn't feel up to it for the time being. He says, tell Miss Lin not to grieve and not to feel homesick. She must think of her grandmother and her aunts as her own family now. He says that her cousins may not be very clever girls, but at least they should be company for her and help to take her mind off things. If she finds anything at all here to distress her, she is to speak up at once. She mustn't feel like an outsider. She is to make herself completely at home."

Dai-yu stood up throughout this recital and murmured polite assent whenever assent seemed indicated. She then sat for about another quarter of an hour before rising to take her leave. Her Aunt Xing was very pressing that she should have a meal with her before she went, but Dai-yu smilingly replied that though it was very kind of her aunt to offer, and though she ought really not to refuse, nevertheless she still had to pay her respects to her Uncle Zheng, and feared that it would be disrespectful if she were to arrive late. She hoped that she might accept on another occasion and begged her aunt to excuse her.

"In that case, never mind," said Lady Xing, and instructed the old nurses to see her to her Uncle Zheng's in the same carriage she had come by. Dai-yu formally took her leave, and Lady Xing saw her as far as the inner gate, where she issued a few more instructions to the servants and watched her niece's carriage out of sight before returning to her rooms.

Presently they re-entered the Rong mansion proper and Dai-yu got down from the carriage. There was a raised stone walk running all the way up to the main gate, along which the old nurses now conducted her. Turning right, they led her down a roofed passage-way along the back of a south-facing hall, then through an inner gate into a large courtyard.

The big building at the head of the courtyard was connected at each end to galleries running through the length of the side buildings by means of "stag's head" roofing over the corners. The whole formed an architectural unit of greater sumptuousness and magnificence than anything Dai-yu had yet seen that day, from which she concluded that this must be the main inner hall of the whole mansion.

High overhead on the wall facing her as she entered the hall was a great blue board framed in gilded dragons, on which was written in large gold characters

THE HALL OF EXALTED FELICITY

with a column of smaller characters at the side giving a date and the words ".... written for Our beloved Subject, Jia Yuan,.Duke of Rong-guo", followed by the Emperor's private seal, a device containing the words "kingly cares" and "royal brush" in archaic seal-script.

A long, high table of carved red sandalwood, ornamented with dragons, stood against the wall underneath. In the centre of this was a huge antique bronze ding, fully a yard high, covered with a green patina. On the wall above the ding hung a long vertical scroll with an ink-painting of a dragon emerging from clouds and waves, of the kind often presented to high court officials in token of their office. The ding was flanked on one side by a smaller antique bronze vessel with a pattern of gold inlay and on the other by a crystal bowl. At each side of the table stood a row of eight yellow cedar-wood armchairs with their backs to the wall; and above the chairs hung, one on each side, a pair of vertical ebony boards inlaid with a couplet in characters of gold:

(on the right-hand one)

May the jewel of learning shine in this house mote effulgently than the sun and moon.

(on the left-hand one)

May the insignia of honour glitter in these halls more brilliantly than the starry sky.

This was followed by a colophon in smaller characters:

With the Respectful Compliments of your Fellow-

Student, Mu Shi, Hereditary Prince of Dong-an.

Lady Wang did not, however, normally spend her leisure hours in this main reception hall, but in a smaller room on the east side of the same building. Accordingly the nurses conducted Dai-yu through the door into this side apartment.

Here there was a large kang underneath the window, covered with a scarlet Kashmir rug. In the middle of the kang was a dark-red bolster with a pattern of medallions in the form of tiny dragons, and a long russet-green seating strip in the same pattern. A low rose-shaped table of coloured lacquer-work stood at each side. On the left-hand one was a small, square, four4egged ding, together with a bronze ladle, metal chopsticks, and an incense container. On the right-hand one was a narrow-waisted Ru-ware imitation gu with a spray of freshly cut flowers in it.

In the part of the room below the kang there was a row of four big chairs against the east wall. All had footstools in front of them and chair-backs and seat-covers in old rose brocade sprigged with flowers. There were also narrow side-tables on which tea things and vases of flowers were arranged, besides other furnishings which it would be superfluous to enumerate.

The old nurses invited Dai-yu to get up on the kang; but guessing that the brocade cushions arranged one on each side near the edge of it must be her uncle's and aunt's places, she deemed it more proper to sit on one of the chairs against the wall below. The maids in charge of the apartment served tea, and as she sipped it Dai-yu observed that their clothing, makeup, and deportment were quite different from those of the maids she had seen so far in other parts of the mansion.

Before she had time to finish her tea, a smiling maid came in wearing a dress of red damask and a black silk sleeveless jacket which had scalloped borders of some coloured material.

"The Mistress says will Miss Lin come over to the other side, please."

The old nurses now led Dai-yu down the east gallery to a reception room at the side of the courtyard. This too had a king. It was bisected by a long, low table piled with books and tea things. A much-used black satin back-rest was pushed up against the east wall. Lady Wang was seated on a black satin cushion and leaning against another comfortable4ooking back-rest of black satin somewhat farther forward on the opposite side.

Seeing her niece enter, she motioned her to sit opposite her on the kang, but Dai-yu felt sure that this must be her Uncle Zheng's place. So, having observed a row of three chairs near the kang with covers of flower-sprigged brocade which looked as though they were in fairly constant use, she sat upon one of those instead. Only after much further pressing from her aunt would she get up on the kang, and even then she would only sit beside her and not in the position of honour opposite.

"Your uncle is in retreat today," said Lady Wang. "He will see you another time. There is, however, something I have got to talk to you about. The three girls are very well-behaved children, and in future, when you are studying or sewing together, even if once in a while they may grow a bit high-spirited, I can depend on them not to go too far. There is only one thing that worries me. I have a little monster of a son who tyrannizes over all the rest of this household. He has gone off to the temple today in fulfillment of a vow and is not yet back; but you will see what I mean this evening. The thing to do is never to take any notice of him. None of your cousins dare provoke him."

Dai-yu had long ago been told by her mother that she had a boy cousin who was born with a piece of jade in his mouth and who was exceptionally wild and naughty. He hated study and liked to spend all his time in the women's apartments with the girls, but because Grandmother Jia doted on him so much, no one ever dared to correct him. She realized that it must be this cousin her aunt was now referring to.

"Do you mean the boy born with the jade, Aunt?" she asked. "Mother often told me about him at home. She told me that he was one year older than me and that his name was Bao-yu. But she said that though he was very willful, he always behaved very nicely to girls. Now that I am here, I suppose I shall be spending all my time with my girl cousins and not in the same part of the house as the boys. Surely there will be no danger of my provoking him?"

Lady Wang gave a rueful smile. "You little know how things are here! Bao-yu is a law unto himself. Because your grand-mother is so fond of him she has thoroughly spoiled him. When he was little he lived with the girls, so with the girls he remains now. As long as they take no notice of him, things run quietly enough. But if they give him the least encouragement, he at once becomes excitable, and then there is no end to the mischief he may get up to. That is why I counsel you to ignore him. He can be all honey-sweet words one minute and ranting and raving like a lunatic the next. So don't believe anything he says."

Dai-yu promised to follow her aunt's advice.

Just then a maid came in with a message that "Lady Jia said it was time for dinner", whereupon Lady Wang took Dai-yu by the hand and hurried her out through a back door. Passing along a verandah which ran beneath the rear eaves of the hall they came to a corner gate through which they passed into an alley-way running north and south. At the south end it was traversed by a narrow little building with a short passage-way running through its middle. At the north end was a white painted screen wall masking a medium-sized gateway leading to a small courtyard in which stood a very little house.

"That," said Lady Wang, pointing to the little house, "is where your Cousin Lian's wife, Wang Xi-feng, lives, in case you want to see her later on. She is the person to talk to if there is anything you need."

There were a few young pages at the gate of the courtyard who, when they saw Lady Wang coming, all stood to attention with their hands at their sides.

Lady Wang now led Dai-yu along a gallery, running from east to west, which brought them out into the courtyard behind Grandmother Jia's apartments. Entering these by a back entrance, they found a number of servants waiting there who, as soon as they saw Lady Wang, began to arrange the table and chairs for dinner. The ladies of the house themselves took part in the service. Li Wan brought in the cups, Xi-feng laid out the chopsticks, and Lady Wang brought in the soup.

The table at which Grandmother Jia presided, seated alone on a couch, had two empty chairs 6n either side. Xi-feng tried to seat Dai-yu in the one on the left nearer to her grandmother —an honour which she strenuously resisted until her grandmother explained that her aunt and her elder cousins" wives would not be eating with them, so that, since she was a guest, the place was properly hers. Only then did she ask permission to sit, as etiquette prescribed. Grandmother Jia then ordered Lady Wang to be seated. This was the cue for the three girls to ask permission to sit. Ying-chun sat in the first place on the right opposite Dai-yu, Tan-chun sat second on the left, and Xi-chun sat second on the right.

While Li Wan and Xi-feng stood by the table helping to distribute food from the dishes, maids holding fly-whisks, spittoons, and napkins ranged themselves on either side. In addition to these, there were numerous other maids and serving-women in attendance in the outer room, yet not so much as a cough was heard throughout the whole of the meal.

When they had finished eating, a maid served each diner with tea on a little tray. Dai-yu's parents had brought their daughter up to believe that good health was founded on careful habits, and in pursuance of this principle, had always insisted that after a meal one should allow a certain interval to elapse before taking tea in order to avoid indigestion. However, she could see that many of the rules in this household were different from the ones she had been used to at home; so, being anxious to conform as much as possible, she accepted the tea. But as she did so, another maid preferred a spittoon, from which she inferred that the tea was for rinsing her mouth

with. And it was not, in fact, until they had all rinsed out their mouths and washed their hands that another lot of tea was served, this time for drinking.

Grandmother Jia now dismissed her lady servers, observing that she wished to enjoy a little chat with her young grand children without the restraint of their grown-up presence.

Lady Wang obediently rose to her feet and, after exchanging a few pleasantries, went out, taking Li Wan and Wang Xi-feng with her.

Grandmother Jia asked Dai-yu what books she was studying.

"The Four Books," said Dai-yu, and inquired in turn what books her cousins were currently engaged on.

"Gracious, child, they don't study books," said her grandmother; "they can barely read and write!"

While they were speaking, a flurry of footsteps could be heard outside and a maid came in to say that Bao-yu was back.

"I wonder," thought Dai-yu, "just what sort of graceless creature this Bao-yu is going to be!"

The young gentleman who entered in answer to her unspoken question had a small jewel-encrusted gold coronet on the top of his head and a golden headband low down over his brow in the form of two dragons playing with a large pearl.

He was wearing a narrow-sleeved, full-skirted robe of dark red material with a pattern of flowers and butterflies in two shades of gold. It was confined at the waist with a court girdle of coloured silks braided at regular intervals into elaborate clusters of knotwork and terminating in long tassels.

Over the upper part of his robe he wore a jacket of slate-blue Japanese silk damask with a raised pattern of eight large medallions on the front and with tasselled borders.

On his feet he had half4ength dress boots of black satin with thick white soles.

As to his person, he had:

a face like the moon of Mid-Autumn,

a complexion like flowers at dawn,

a hairline straight as a knife-cut,

eyebrows that might have been painted by an artist's brush,

a shapely nose, and eyes clear as limpid pools,

that even in anger seemed to smile,

and, as they glared, beamed tenderness the while.

Around his neck he wore a golden torque in the likeness of a dragon and a woven cord of coloured silks to which the famous jade was attached.

Dai-yu looked at him with astonishment. How strange! How very strange! It was as though she had seen him somewhere before, he was so extraordinarily familiar. Bao-yu went straight past her and saluted his grandmother, who told him to come after he had seen his mother, whereupon he turned round and walked straight out again.

Quite soon he was back once more, this time dressed in a completely different outfit.

The crown and circlet had gone. She could now see that his side hair was dressed in a number of small braids plaited with red silk, which were drawn round to join the long hair at the back in a single large queue of glistening jet black, fastened at intervals from the nape downwards with four enormous pearls and ending in a jewelled gold clasp. He had changed his robe and jacket for a rather more worn-looking rose-coloured gown, sprigged with flowers. He wore the gold torque and his jade as before, and she observed that the collection of objects round his neck had been further augmented by a padlock-shaped amulet and a lucky charm. A pair of ivy-coloured embroidered silk trousers were partially visible beneath his gown, thrust into black and white socks trimmed with brocade. In place of the formal boots he was wearing thick-soled crimson slippers.

She was even more struck than before by his fresh complexion. The cheeks might have been brushed with powder and the lips touched with rouge, so bright was their natural colour.

His glance was soulful,

yet from his lips the laughter often leaped;

a world of charm upon that brow was heaped;

a world of feeling from those dark eyes peeped.

In short, his outward appearance was very fine. But appearances can be misleading. A perceptive poet has supplied two sets of verses, to be sung to the tune of Moon On West River, which contain a more accurate appraisal of our hero than the foregoing descriptions.

I

Oft-times he sought Out what would make him sad;

Sometimes an idiot seemed and sometimes mad.

Though outwardly a handsome sausage-skin,

He proved to have but sorry meat within.

A harum-scarum, to all duty blind,

A doltish mule, to study disinclined;

His acts outlandish and his nature queer;

Yet not a whit cared he how folk might jeer!

2

Prosperous, he could not play his part with grace,

Nor, poor, bear hardship with a smiling face.

So shamefully the precious hours he'd waste

That both indoors and out he was disgraced.

For uselessness the world's prize he might bear;

His gracelessness in history has no peer.

Let gilded youths who every dainty sample

Not imitate this rascal's dire example!

"Fancy changing your clothes before you have welcomed the visitor!" Grandmother Jia chided indulgently on seeing Bao-yu back again. "Aren't you going to pay your respects to your cousin?"

Bao-yu had already caught sight of a slender, delicate girl whom he surmised to be his Aunt Lin's daughter and quickly went over to greet her. Then, returning to his place and taking a seat, he studied her attentively. How different she seemed from the other girls he knew!

Her mist-wreathed brows at first seemed to frown, yet were not frowning;

Her passionate eyes at first seemed to smile, yet were not merry.

Habit had given a melancholy cast to her tender face;

Nature had bestowed a sickly constitution on her delicate frame.

Often the eyes swam with glistening tears;

Often the breath came in gentle gasps.

In stillness she made one think of a graceful flower reflected in the water;

In motion she called to mind tender willow shoots caressed by the wind.

She had more chambers in her heart than the martyred Bi Gan;

And suffered a tithe more pain in it than the beautiful Xi Shi.

Having completed his survey, Bao-yu gave a laugh. "I have seen this cousin before."

"Nonsense!" said Grandmother Jia. "How could you P055-ibly have done?"

"Well, perhaps not," said Bao-yu, "but her face seems 80 familiar that I have the impression of meeting her again after a long separation."

"All the better," said Grandmother Jia. "That means that you should get on well together."

Bao-yu moved over again and, drawing a chair up beside Dai-yu, recommenced his scrutiny.

Presently: "Do you study books yet, cousin?"

"No," said Dai-yu. "I have only been taking lessons for a year or so. I can barely read and write."

"What's your name?"

Dai-yu told him.

"What's your school-name?"

"I haven't got one."

Bao-yu laughed. "I'll give you one, cousin. I think 'Frowner' would suit you perfectly."

"Where's your reference?" said Tan-chun.

"In the Encyclopedia of Men and Objects Ancient and Modern it says that somewhere in the West there is a mineral called 'dai' which can be used instead of eye-black for painting the eyebrows with. She has this 'dai' in her name and she knits her brows together in a little frown. I think it's a splendid name for her!"

"I expect you made it up," said Tan-chun scornfully.

"What if I did?" said Bao-yu. "There are lots of made-up things in books—apart from the Four Books, of course."

He returned to his interrogation of Dai-yu.

"Have you got a jade?"

The test of the company were puzzled, hut Dai-yu at once divined that he was asking her if she too had a jade like the one he was born with.

"No," said Dal-yu. "That jade of yours is a very rare object. You can't expect everybody to have one."

This sent Bao-yu off instantly into one of his mad fits. Snatching the jade from his neck he hurled it violently on the floor as if to smash it and began abusing it passionately.

"Rare object! Rare object! What's so lucky about a stone that can't even tell which people are better than others? Beastly thing! I don't want it!"

The maids all seemed terrified and rushed forward to pick it up, while Grandmother Jia clung to Bao-yu in alarm.

"Naughty, naughty boy! Shout at someone or strike them if you like when you are in a nasty temper, but why go smashing that precious thing that your very life depends on?"

"None of the girls has got one," said Bao-yu, his face streaming with tears and sobbing hysterically. "Only I have got one. It always upsets me. And now this new cousin comes here who is as beautiful as an angel and she hasn't got one either; so I know it can't be any good."

"Your cousin did have a jade once," said Grandmother Jia, coaxing him like a little child, "but because when Auntie died she couldn't bear to leave her little girl behind, they had to let her take the jade with her instead. In that way your cousin could show her mamma how much she loved her by letting the jade be buried with her; and at the same time, whenever Auntie's spirit looked at the jade, it would be just like looking at her own little girl again.

"So when your cousin said she hadn't got one, it was only because she didn't want to boast about the good, kind thing she did when she gave it to her mamma. Now you put yours on again like a good boy, and mind your mother doesn't find Out how naughty you have been."

So saying, she took the jade from the hands of one of the maids and hung it round his neck for him. And Bao-yu, after reflecting for a moment or two on what she had said, offered no further resistance.

At this point some of the older women came to inquire what room Dai-yu was to sleep in.

"Move Bao-yu into the closet-bed with me," said Grandmother Jia, "and put Miss Lin for the time being in the green muslin summer-bed. We had better wait until spring when the last of the cold weather is over before seeing about the rooms for them and getting them settled permanently."

"Dearest Grannie," said Bao-yu pleadingly, "I should be perfectly all right next to the summer-bed. There's no need to move me into your room. I should only keep you awake."

Grandmother Jia, after a moment's reflection, gave her consent. She further gave instructions that Dai-yu and Bao-yu were each to have one nurse and one maid to sleep with them. The rest of their servants were to do night duty by rota in the adjoining room. Xi-feng had already sent across some lilac-coloured hangings, brocade quilts, satin coverlets and the like for Dai-yu's bedding.

Dai-yu had brought only two of her own people with her from home. One was her old wet-nurse Nannie Wang, the other was a little ten-year-old maid called Snowgoose. Considering Snowgoose too young and irresponsible and Nannie Wang too old and decrepit to be of much real service, Grandmother Jia gave Dai-yu one of her own maids, a body-servant of the second grade called Nightingale. She also gave orders that Dai-yu and Bao-yu were to be attended in other respects exactly like the three girls: that is to say, apart from the one wet-nurse, each was to have four other nurses to act as chaperones, two maids as body-servants to attend to their washing, dressing, and so forth, and four or five maids for dusting and cleaning, running errands and general duties.

These arrangements completed, Nannie Wang and Nightingale accompanied Dai-yu to bed inside the tent-like summer-bed, while Bao-yu's wet-nurse Nannie Li and his chief maid Aroma settled him down for the night in a big bed on the other side of the canopy.

Like Nightingale, Aroma had previously been one of Grandmother Jia's own maids. Her real name was Pearl. Bao-yu's grandmother, fearful that the maids who already waited on her darling boy could not be trusted to look after him properly, had picked out Pearl as a girl of tried and conspicuous fidelity and put her in charge over them. It was Bao-yu who was responsible for the curious name "Aroma". Discovering that Pearl's surname was Hua, which means "Flowers", and having recently come across the line

Related articles:

CHAPTER 1 (The Story of the Stone-translated by David Hawkes)

- Category:

- ▸ The Story of the Stone

CHAPTER 1Zhen Shi-yin makes the Stone's acquaintance in a dreamAnd Jia Yu-cun finds that poverty is not incompatible with romantic feelingGENTLE READER,What, you may ask, was the origin of this book?Though the answer to this question may at first seem to border on...

|

CHAPTER 2 (The Story of the Stone-translated by David Hawkes)

- Category:

- ▸ The Story of the Stone

CHAPTER 2A daughter of the Jias ends her daysin Yangchow cityAnd Leng Zi-xing discourses on the Jias ofRong-guo HouseHearing the clamour of yamen runners outside, Feng Su hurried to the door, his face wreathed in smiles, to ask what they wanted. "Tell Mr Zhen to step ou...

|