CHAPTER 4 (The Golden Lotus) Ximen Qing Attains His End

- Posted on: 2023-01-16

- |

- Views: 488

- |

- Category:

- ▸ The Golden Lotus

CHAPTER 4

Ximen Qing Attains His End

The sun streams through the painted doorway into the bedchamber.

There stands a maiden whom no gold can buy.

She leans against the door

Her lovely eyes, like beams of sunshine, seek to pursue her lover

But he has gone so far, her tender feet may never hope to follow.

Old woman Wang took the money and started for the door. Smiling, she said to Jinlian, "I must go to the street to buy a jar of wine; you will keep his Lordship company, won't you? If there is a drop left in the jar, warm two cups and drink them with him. The best wine is to be had in East Street. I shall have to go there for it, so I may be away some little time."

"Really I can't drink any more," Pan Jinlian cried. "Please don't go on my account."

"You and his Lordship are no longer strangers," said the old woman, "and you have nothing else to do. Drink a cup of wine with him. Why should you be afraid?"

With her lips Jinlian said she did not wish to drink, but her body told another story. The old woman shut the door and fastened it on the outside with a chain, imprisoning the two young people in her room. Then outside in the roadway, she sat down and began to roll some thread. Jinlian saw the old woman go, and pulled her chair to one side. As she settled down again, she glanced swiftly at Ximen Qing. He was sitting on the other side of the table, his eyes wide open, staring at her. At last he managed to speak.

"I forgot to ask your honorable name."

The woman bowed, and answered, smiling, "My unworthy name is Wu."

Ximen Qing pretended that he had not heard properly. "Did you say Du?" he said. Jinlian looked up, and said in a very soft voice, "I did not think you were deaf, Sir."

"I am sorry," Ximen said, "it was my mistake. You said 'Wu.' There are not many people called Wu in Qinghe. There is indeed one fellow who sells cakes outside the Town Hall, but he is no bigger than my thumb. His name is Wu, Master Wu Da. Is he a relative of yours by any chance?"

Jinlian flushed. "He is my husband," she said, hanging her head.

Ximen Qing was silent for a long time, and seemed to be thinking very seriously. "How sad! How wrong!" he murmured at last. Jinlian smiled, and glanced at him.

"You have no reason to complain. Why should you say, 'How sad!'?"

"I was thinking how sad it must be for you," he said. He muttered many things, almost unintelligibly. Jinlian still looked down. She played with her skirt, nibbled at her sleeves, and bit her lips, sometimes talking, sometimes glancing slyly at him. Ximen pretended to find the heat trying, and took off his green silk coat.

"Would you mind putting my coat on the old lady's bed?" he said. Jinlian did not offer to take the coat. Keeping her head still turned away, she played with her sleeves and smiled. "Is there anything wrong with your own hands?" she said. "Why do you ask me to do things for you?" Ximen Qing laughed.

"So you won't do a little thing like that for me? Well, I suppose I must do it myself." He leaned over the table and put his coat on the bed. As he did so, he brushed the table with his sleeve and knocked down a chopstick. Luck favored him; the chopstick came to rest beneath the woman's skirt. Ximen, who had already drunk more wine than was good for him, invited her to join him. Then he wanted his chopsticks to help her to some of the dishes. He looked about. One of them was missing. Jinlian looked down, pushed the chopstick with her toe, and said, laughing, "Isn't this it?" Ximen Qing went to her, and bent down. "Ah, here it is!" he cried, but instead of picking up the chopstick, he took hold of her embroidered shoe.

Jinlian laughed. "I shall shout, if you are so naughty."

"Be kind to me, Lady," Ximen said, going down on his knees. As he spoke, he gently stroked her silken garments.

"It is horrid of you to pester me so," Jinlian cried. "I shall box your ears."

"Lady," he said, "if your blows should cause my death, it would be a happy end."

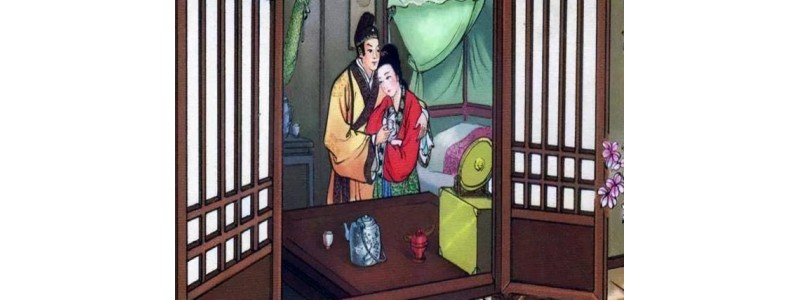

Without giving her time to object, he carried her to old woman Wang's bed, took off his clothes and, after unloosing her girdle, lay down with her. Their happiness reached its culmination.

In the days when Jinlian had performed the act of darkness with Zhang, that miserable old man had never been able to offer any substantial contribution to the proceedings, and not once had she been satisfied. Then she married Wu Da. You may imagine the prowess that might be expected from Master Tom Thumb. It could hardly be described as heroic. Now she met Ximen Qing, whose capacity in such matters was unlimited and whose skill was exceptionally refined and cunning.

The mandarin ducks, with necks entwined, sport upon the water.

The phoenix and his mate, their heads close pressed together, fly among the blossoms.

Joyful and tireless, the tree puts forth twin branches

The girdle, tied in a lovers' knot, is full of sweetness.

He, the red-lipped one, thirsts for a close embrace

She, of the powdered cheeks, awaits it eagerly.

The silken hose are raised on high

And two new moons appear above his shoulders.

The golden hairpins fall

And on the pillow rests a bank of lowering clouds.

They swear eternal oaths by ocean and by mountain

Seeking a thousand new delights.

The clouds are bashful and the rain is shy

They play ten thousand naughty tricks.

"Qia Qia," the oriole cries.

Each sucks the nectar from the other's lips.

The cherry lips breathe lightly, lightly.

In those willowy hips the passion beats

The mocking eyes are bright like stars

Tiny drops of sweat are like a hundred fragrant pearls

The sweet full breasts tremble

The dew, like a gentle stream, reaches the heart of the peony

They taste the joys of love in perfect harmony

For stolen joys, in truth, are ever the most sweet.

Just when they had done and were putting on their clothes again, old woman Wang pushed open the door and came in, clapping her hands as though she had never been more surprised in her life.

"A fine state of affairs," she said. Ximen Qing and Jinlian were extremely embarrassed.

"Oh, splendid, splendid!" the old woman said to Jinlian. "I asked you to come here to make clothes, not to make love with someone else's husband. If your Wu Da found this out, he would blame me. I shall have to go and explain the matter to him at once." She turned, and started out. Jinlian caught her quickly by the skirt. She hid her blushing face and could only get out a single sentence: "Spare me, Stepmother."

"You must make me a promise, then," the old woman said. "From this day forward, you must deceive Wu Da and give his Lordship here whatever he desires. If I call you early, you must come early. If I call you late, you must come late. Then I will say no more about it. But, if there should be a day when you do not come, I shall tell Wu Da."

Jinlian was so abashed that she could find nothing to say. "Well," said the old woman, "what are you going to do about it? I must have an answer now." "I will come," the woman whispered. Old woman Wang turned to Ximen Qing. "I need say no more to you, Sir. This is a fine piece of work, and you owe it all to me. You must not forget your promise. You must keep your word. If you try to wriggle out of it, I shall be compelled to speak to Wu Da."

"Don't worry, Stepmother," Ximen said, "I shall not go back on my word."

"I haven't too much confidence in either of you," old woman Wang said. "Give me a pledge of some sort and then I'll believe you."

Ximen Qing took a golden pin from his head and set it in Jinlian's hair. She took it out again and put it in her sleeve, for she was afraid that if she went home wearing it, Wu Da would wish to know where it had come from. She hesitated to produce any pledge herself, but the old woman caught her by the sleeve and, finding a white silk handkerchief, handed it to Ximen Qing. Then they all drank several cups of wine. By this time it was getting dark and, saying that it was time for her to go home, Jinlian said good-bye to old woman Wang and Ximen Qing and went to her house by the back way. She pulled down the blind and, soon afterwards, Wu Da came in.

Old woman Wang looked at Ximen Qing.

"Did I play my cards well?" she said.

"No one could have done better," said Ximen.

"Were you satisfied?"

"Perfectly."

"She comes of singing girl stock," the old woman said, "and she must have had plenty of experience. I am very proud that I have been able to bring you two together, especially since I did it all by my own cleverness. Mind you give me what you promised."

"I will send you the silver as soon as I reach home."

"My eyes have seen the banner of victory and my ears have heard a sweet message," the old woman said, "but don't wait until my coffin is being carried out for burial, and then send money for the choirboys."

Ximen Qing laughed. He saw that the street was deserted, put on his eyeshades, and went home.

The next day he came again to the old woman's house. The old lady made tea for him and asked him to sit down. He took ten taels of silver from his sleeve and gave it to her. Money seems to produce an extraordinary effect upon people everywhere. As soon as the old woman's black eyes beheld this snow-white silver, she was as happy as could be. She took it, and twice made reverence to him. "I thank you, Sir," she said, "with all my heart."

"Wu Da is still at home," she continued, "but I will go over to his house and pretend I wish to borrow a gourd." She went by the back way to her neighbor's house. Jinlian was giving her husband his breakfast when she heard the knocking at the door, and told Ying'er to see who was there. It is Grandmother Wang," the girl said, "she has come to borrow a water gourd."

"I will lend you a water jug, Stepmother," Jinlian said, "but won't you come in and sit down a while?"

"There is nobody to look after my house," the old woman said, beckoning with her finger to Jinlian, thus giving her to understand that Ximen Qing had come. She took the gourd and went away, and Jinlian hustled her husband over his breakfast and packed him off with his baskets. She went upstairs and redressed herself, putting on beautiful new clothes, and told Ying'er to watch the house. "I am going to your Grandmother Wang's, but I shall be back in a moment. If your father comes home, let me know at once or it will be the worse for your little bottom." She went to the tea shop.

Jinlian came, and to Ximen Qing it seemed that she had come straight down from Heaven. Side by side, close pressed together, they sat. Old woman Wang gave them tea. "Did Wu Da ask you any questions when you got home yesterday?" she said.

"He asked me if I had finished your clothes, and I told him that the funeral shoes and socks had still to be made."

The old woman hastily set wine before them, and they drank together, very happily. Ximen Qing delighted in every detail of the woman's form. She seemed to him even more beautiful than when he had first seen her. The little wine she had taken brought roses to her pale face and, with her cloudlike hair, she might have been a fairy, more beautiful than Chang E.

Ximen Qing could not find words to express his admiration. He gathered her in his arms, and lifted her skirts that he might see her dainty feet. She was wearing shoes of raven-black silk, no broader than his two fingers. His heart was overflowing with delight. Mouth to mouth they drank together, and smiled. Jinlian asked how old he was. "I am twenty-seven. I was born on the twenty-eighth day of the seventh month." Then she said, "How many ladies are there in your household?" and he said, "Besides the mistress of my house, there are three or four, but with none of them am I really satisfied." Again she asked, "How many sons have you?" and he answered, "I have no sons, only one little girl who is shortly to be married." Then it was his turn to ask her questions.

He took from his sleeve a box, gilded on the outside and silver within. There were fragrant tea leaves in it and some small sweetmeats. Placing some of them on his tongue, he passed them to her mouth. They embraced and hugged one another; their cries and kissings made noise enough, but old woman Wang went in and out, carrying dishes and warming the wine, and paid not the slightest attention to them. They played their amorous games without any interference from her. Soon they had drunk as much as they desired, and a fit of passion swept over them. Ximen Qing's desire could no longer be restrained; he disclosed the treasure that sprang from his loins, and made the woman touch it with her delicate fingers. From his youth upwards he had constantly played with the maidens who live in places of ill-fame, and he was already wearing the silver clasp that had been washed with magic herbs. Upstanding, it was, and flushed with pride, the black hair strong and bristling. A mighty warrior in very truth.

A warrior of stature not to be despised

At times a hero and at times a coward.

Who, when for battle disinclined,

As though in drink sprawls to the east and west.

But, when for combat he is ready,

Like a mad monk he plunges back and forth

And to the place from which he came returns.

Such is his duty.

His home is in the loins, beneath the navel.

Heaven has given him two sons

To go wherever he goes

And, when he meets an enemy worthy of his steel,

He will attack, and then attack again.

Then Jinlian took off her clothes. Ximen Qing fondled the fragrant blossom. No down concealed it; it had all the fragrance and tenderness of fresh-made pastry, the softness and the appearance of a new-made pie. It was a thing so exquisite that all the world would have desired it.

Tender and clinging, with lips like lotus petals

Yielding and gentle, worthy to be loved.

When it is happy, it puts forth its tongue

And welcomes with a smile.

When it is weary, it is content

To stay where Nature put it

At home in Trouser Village

Among the scanty herbage.

But, when it meets a handsome gallant

It strives with him and says no word.

After that day, Jinlian came regularly to the old woman's house to sport with Ximen Qing. Love bound them together as it were with glue; their minds and hearts were united as if with gum.

There is an old saying: "Good news never leaves the house, but ill news spreads a thousand miles." It was not long before all the neighbors knew what was going on. Only Wu Da remained ignorant.

In Qinghe there lived a boy called Qiao; he was about fifteen years old. As he had been born in Yunzhou, where his father was on military service, he was called Yun'ge. His father was now grown old, and they lived together alone. The boy was by no means without craft. He kept himself by selling fresh fruits in the different wineshops, and Ximen Qing often gave him small sums of money. One day he had filled his basket with snow-white pears and was carrying them about the streets, on the lookout for his patron. Somebody he chanced to meet said to him, "Yun'ge, I can tell you where to find him."

"Where can I find him, Uncle?" the boy said. "Tell me if you please."

"Ximen," the man said, "is carrying on with the wife of Wu Da, the cake seller. Every day he goes to old woman Wang's house in Amethyst Street. Most likely you will find him there now. There is nothing to prevent you going straight into the room."

Yun'ge thanked the man, and went along Amethyst Street with his basket till he came to old woman Wang's tea shop. The old woman was sitting on a small chair by the door, making thread. The boy put down his basket, looked at her, and said, "Greetings to you, Stepmother."

"What do you want, Yun'ge?" the old woman said.

"I have come to see his Lordship in the hope of getting thirty or fifty cash to help support my father," the boy told her.

"What 'Lordship' are you talking about?" asked the old woman.

"You know him."

"Well, I suppose every gentleman has some sort of a name," the old woman said.

"This gentleman's name has two characters in it."

"What two characters?"

"You are trying to fool me," Yun'ge said. "It is his Lordship Ximen to whom I am going to speak." He started to go into the house. The old woman caught him. "Where are you going, you little monkey? Don't you know the difference between the inside and the outside of people's houses?"

"I shall find him in the room," the boy said.

The old woman cursed him. "What makes you think you will find his Lordship in my house, you little rascal?"

"Stepmother, don't try to keep all the pickings for yourself. Leave a little gravy for me. I know all about it."

"What do you know?" the old woman cried. "You are a young scoundrel."

"And you are one of those people who would scrape a bowl clean with a knife. You don't mean to lose even a single drop of gravy. If I began to talk about this business, I shouldn't be surprised if my brother, the cake seller, had something to say about it."

This made the old woman furious. She was touched to the quick. "You little monkey," she screamed, "how dare you come to my house to let off your farts."

"Little monkey I may be," said Yun'ge, "but you're an old whoremonger, you old lump of dog meat."

The old woman caught him and boxed his ears twice.

"Why are you hitting me?" cried the boy.

"You son of a thief, you little monkey, make a noise like that and I'll thrash you out of the place."

"You knavish old scorpion," Yun'ge cried, "you have no right to beat me." The old woman struck him again, and drove him out into the street, tossing his basket after him. The pears rolled all over the street, four here and five there. There was nothing the little monkey could do. He grumbled and cried as he picked them up. He shook his fist in the direction of the tea shop, and shouted, "Wait, you old worm! When I've told about this, you will be ruined, and then there will be nothing at all for you."

The young monkey picked up his basket and went off to the street to see if he could find Wu Da.

- Tags:

- Golden Lotus

- Ximen Qing

Related articles:

CHAPTER 1 (The Golden Lotus) The Brotherhood of Rascals

- Category:

- ▸ The Golden Lotus

The Golden LotusCHAPTER 1When wealth has taken wing, the streets seem desolate.The strains of flute and stringed zither are heard no more.The brave long sword has lost its terror; its splendor is tarnished.The precious lute is broken, faded its golden star.The marble...

|

CHAPTER 2 (The Golden Lotus) Pan Jinlian

- Category:

- ▸ The Golden Lotus

CHAPTER 2Pan JinlianWu Song went to the inn near the Town Hall, packed his baggage and his bedclothes, and told a soldier to carry them to his brother's house. When Pan Jinlian saw him coming, she was as delighted as if she had discovered a hidden treasure. She bustl...

|

CHAPTER 3 (The Golden Lotus) The Old Procuress

- Category:

- ▸ The Golden Lotus

CHAPTER 3 The Old ProcuressXimen Qing was desperately anxious to possess Pan Jinlian. He gave the old woman no peace."Stepmother," he said, "if you bring this business to a happy end, I will give you ten taels of silver.""Sir," said the old woman, "you may have ...

|